Identity Theft Protection Checklist

Patrick’s Privacy Practices Part 1

Recently, I’ve been getting a lot of questions from friends and family about how to secure their digital lives – what services they should use, what settings they should change, and best practices. I published a checklist a couple of years ago to help with these sorts of questions, but it was more technical and long. I’ve updated my recommendations, tried to make them easy to understand, and I’ve split them into the following parts (we’ll add links as each part is published):

- Part 1: Identity Theft Protection Checklist (this blog)

- Part 2: Private Communications for Email and Text Messages

- Part 3: Privacy Guide to Apple Intelligence with ChatGPT

- Part 4: Recommended Privacy Settings and Alternatives for Google, Search, and YouTube

- Part 5: Recommended Privacy Settings for iPhone and MacOS

- Part 6: Privacy and Social Media

- Part 7: Basic Security

There’s no doubt your data has been stolen. So what now? What data was stolen, who has access, and how can they abuse it?

- What data? Your name, address, email, and phone number are likely widely available – at least some of your (encrypted, but potentially recoverable) passwords, too. If you’re in the U.S., it’s likely your social security number, date of birth, and one or more of your credit card numbers are in stolen troves of data from places like Equifax. Your face may be out there, too, associated back with your name. And your location history could be available for sale.

- Who has access? A good deal of this data is held by data aggregators who sell the information, legally, to anyone willing to buy it – from private individuals to law enforcement to big companies. Separately, there are “underground” forums accessible via the Tor browser where hackers buy and sell data on specific people or in big batches. This means much or most of this information is available to anyone with a little cash or with sketchy friends.

- How can the data be abused? I’m not here to scare you, but scammers and stalkers make frequent use of this sort of data, and their choice of targets is somewhat random.

- Tricking you / phishing / vishing: With even just a little bit of information about you, they can use the data to pretend they have an existing relationship with you (as a vendor, for example), to try to get you to pay a fake bill, to follow a bogus link, etc. The more information they have, the more convincing they can make their bogus emails, texts, and calls. (And modern AI is helping them to make these attacks more convincing).

- Identity theft: When scammers have social security numbers, they can take out credit in your name, get bogus tax refunds that you’re liable for (whether you were supposed to get a refund or not), and even take out bank loans. There’s also medical identity theft, which is a growing sector where people use your information to gain access to prescription medications and expensive procedures and leave you holding the bag.

- Warrant-less surveillance: When data is commercially available, law enforcement can purchase it without a warrant, which seems innocuous if you’re not a criminal, but sets up innocent people for being falsely accused of crimes because they have a similar face or were in a similar location to a real criminal.

- Account takeover: Given a login, a password, or information that could be used to confirm your identity (phone number, mother’s maiden name, social security number, etc.), scammers can take over your accounts – log into your email or bank or mobile account, for example. Or call support and impersonate you for the same purpose. If they gain access to your email, they can reset passwords at your bank and elsewhere, even if they don’t have those passwords. Stolen accounts can be used to impersonate you to scam your friends and family, to transfer money out of your accounts, to purchase goods, and more.

The Equifax breach was one of the worst ever.

The Equifax breach was one of the worst ever.

So what can you do to protect yourself?

Unfortunately, the safety of your data is in the hands of companies – your banking, medical, utility, telco, and other vendors that you have to interact with to function in modern society. Companies like T-Mobile just keep getting hacked (video) and coughing up your data with mere slaps on the wrist, at best, for their failures. Outside of encouraging your representatives to create real penalties, there’s little you can do to get companies to take better care of your data.

Fortunately, there are still measures you can take to minimize the harm that can be perpetrated against you using that data.

1. Freeze Your Credit

First, let’s stop people from taking out lines of credit in your name. There’s no perfect solution here, but you can make it much more difficult for scammers by “freezing” your credit. I’ve done this for years, and I highly recommend it, but you should know it’s a pain. You have to go to each credit reporting agency and deal with them separately. And then any time you need to use credit – even when doing something as simple as signing up for a new mobile phone plan – you need to remember to go and temporarily unfreeze your credit first. But it’s worth it because this is the single most important thing you can do to protect yourself.

Follow these links for each of the major credit agencies – it won’t cost you money, only time:

- Freeze your credit at Equifax

- Freeze your credit at TransUnion

- Freeze your credit at Experian

- Freeze your credit at Innovis

- Freeze your credit at NCTUE

- Freeze your credit at Chex

Brian Krebs gives detailed advice on freezes if you’d like to learn more. It’s old, but the best resource I can recommend for going deeper:

- Credit Freezes are Free: Let the Ice Age Begin – Krebs on Security

- Think You’ve Got Your Credit Freezes Covered? Think Again. – Krebs on Security

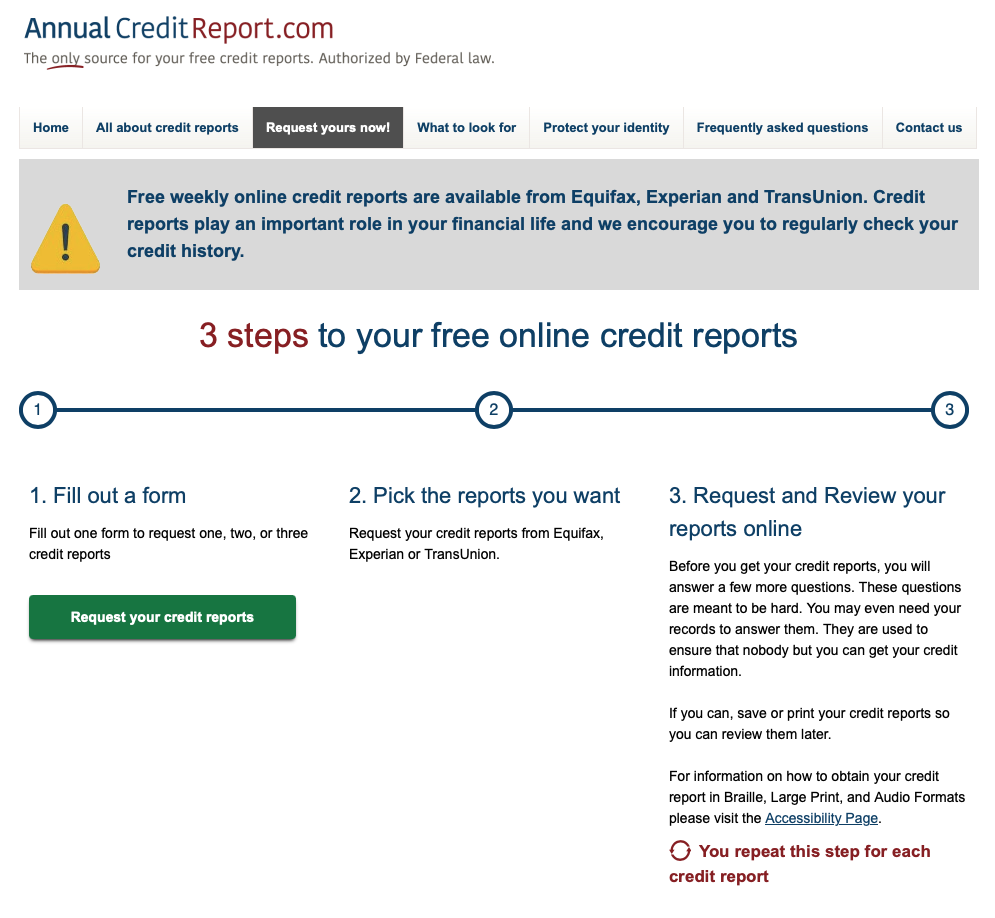

2. Get an Annual Credit Report

Many services provide “fraud alerts” to “monitor your identity.” Companies like Equifax and LifeLock offer it. I find these to be generally worthless. At best, even if they work, they’re reactive, whereas credit freezes are preventive. Do the freeze.

The one exception might be if you get a year of “free credit monitoring” from some vendor who just experienced a breach. What they’re trying to do is to give you identity theft insurance, which is not a bad thing if free to you. The vendor does this to avoid class action lawsuits by heading off any damages. The credit monitoring is not valuable, but the insurance might be. If you do it, just make sure you don’t end up automatically paying for it beyond your free year.

That said, it is a good idea to make sure you know what credit is open in your name as a housekeeping task that can uncover fraud. To do that, you should get a FREE (by law) annual credit report from the top three credit reporting agencies. Pick a time of year that makes sense – when you’re doing your taxes or over New Year’s – so you can form an annual habit.

- Do an annual credit check

3. Setup Identity PINs

When you call support, sometimes companies authenticate you by asking you for your personal information, like your birth date – information that’s easy for anyone to obtain. This is a bad practice, and you should register your concern with the support representative.

Other times, they may authenticate you by sending you a text message. That may sound reasonable, but it turns out that the major carriers are tricked, ALL THE TIME, into transferring a person’s phone number to a phone owned by the scammer. This is called a SIM Swap attack. Suddenly, your incoming calls and texts go to the scammer instead of to you. People known to own Bitcoin or to be wealthy are particularly targeted, but there are victims of all stripes.

If you’re in the U.S. and you use Verizon, AT&T, or T-Mobile, you can apply some extra security to your account by following the links below. I highly recommend you do this. They likely offer similar options if you use a different carrier, but you’ll have to search a bit to figure it out.

- Set up Verizon NumberLock – click the “About Number Lock” tab (if you have Verizon)

- “You can set up Number Lock for free to protect your mobile number from an unauthorized move. That number can’t be moved to another line or carrier unless you remove the lock.”

- Set up an AT&T Account Passcode (if you have AT&T)

- “If you create a unique passcode on your AT&T account, in most cases we’ll require you to provide that passcode before any significant changes can be made, including porting initiated through another carrier.”

- Set up a T-Mobile PIN and Port Out Protection (if you have T-Mobile)

- “T-Mobile recommends setting up a Personal Identification Number (PIN) for when you contact customer service, which is a secure authentication method.”

- “Port Out Protection must be added to each line on your account individually” 🙁

3.1 IRS Protection

Another common way to steal money from you (note: you, not the government) once a scammer has your social security number is to file a fraudulent tax return seeking a refund. As long as they file before you, they can direct that refund to their own account. This creates a ton of trouble for you, but as with the SIM Swap, you can avoid becoming a victim by pre-emptively setting up an Identity Protection PIN with the IRS. Everyone should do this.

- Set up an IRS Identity Protection PIN right away

4. Strong Password Management

Although this part fits better under the “basic security” section coming later, we’re going to cover it now:

- You need to use a password manager to track unique passwords for every website you use so that someone stealing your credentials for one place can’t gain access to your other accounts, too.

- Whenever possible, go into the account settings for your accounts and turn on multi-factor or two-factor authentication. Do this for everything that handles your communication or that has the ability to automatically charge your credit card or manage your finances. Prioritize your bank login, your credit card logins, your email login, and so forth.

If you haven’t used a password manager before, you may need to dedicate some serious time to logging into various accounts and changing passwords to use new, stronger, and unique ones generated by the password manager. You will only need to remember your main password manager password after that. If this is intimidating, ask a trusted neighbor or relative for help.

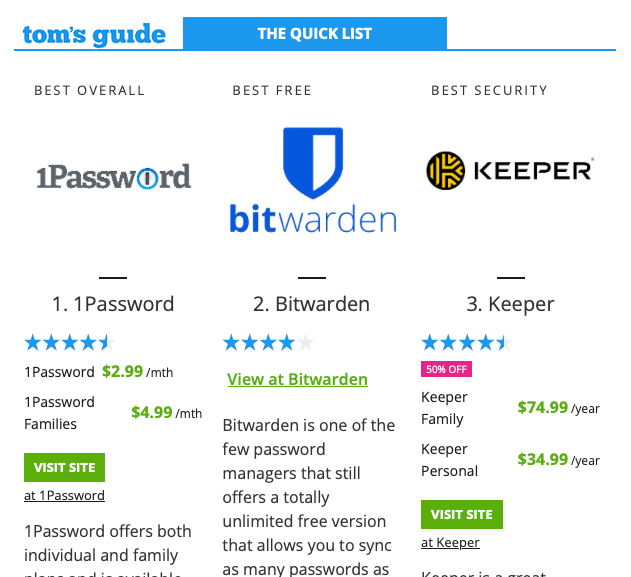

Which password manager to use is a trickier question. I previously used 1Password, and I still recommend it for most people, though it has a monthly fee (actually, most of these do, typically at $1-$3/month). I trust Proton and their ProtonPass product, but haven’t used it. And a lot of people I respect use and recommend Bitwarden.

Personally, I use KeepassXC and Strongbox, which both use the open source Keepass data formats and share an encrypted database and let me use the same database across Mac and Linux.

Here’s what others recommend:

- Wired recommends Bitwarden for most people, 1Password as an upgrade pick, and Dashlane as a “full-featured” option

- Tom’s Guide recommends 1Password as best overall, Bitwarden as the best free, and Keeper as the best security.

- NYT’s Wirecutter recommends 1Password as the top pick and Bitwarden as the budget pick

None of these reviews mention that if you’re 100% in the Apple ecosystem, there’s now a native Apple Passwords app that is a nice option, secure, seamless, and also has no cost beyond what you likely already pay Apple for devices and an iCloud subscription.

- Pick out and use a password manager

- Migrate to all unique and strong passwords

- Enable 2FA/MFA for all sensitive accounts

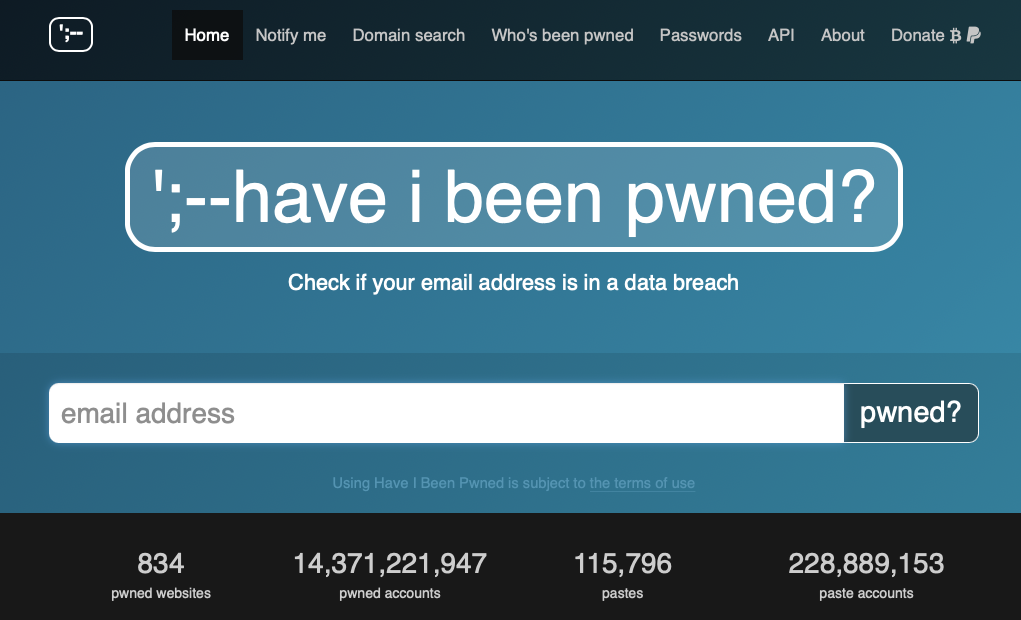

4.1 Breach Monitoring

Now let’s assume you’ve done the hard work and have secured your accounts. You still want to keep an eye out for any changes to those accounts that might indicate they have been compromised. Most password managers have features that do this for you, letting you know when you should change various passwords. But I like to also get an email from the definitive source of hacked data floating around hacker forums:

Have I Been Pwned: Check if your email has been compromised in a data breach

It’s great, it’s private, and it’s a free service that I recommend. If they detect your email address in new repositories of hacked data, they’ll email you. If you get an email about a compromise, don’t freak out; just go to the account affected and change your password.

- Sign up for ”Have I Been Pwned”

5. Reduce Your Data Held by Data Brokers

A data broker is a commercial company that collects as much data on as many people as they can and then sells that data to anyone with money. Sadly, data brokers get hacked all the time, so the data they have leaks to criminals, but they’ll also sell your data to absolutely anyone, which probably includes criminals. So if the bad guys can’t steal your data, they can just buy it.

Data brokers don’t (theoretically) traffic in stolen data, but they do use lots of sketchy ways to get information about you. Free apps sell information to these companies, including your location and spending habits. They get your data in deceptive ways in above-board but largely hidden markets. The collected data gets used for background checks, credit reports, ad targeting, private investigations, and even for simple things like white page lookups of phone numbers.

That may not sound terrible, but they collect everything so they may also know about your church affiliation, job, salary, what you like to buy, where you like to go, what doctors you pay or visit, and so on. It’s creepy, and anyone can purchase the data including the U.S. Government, who doesn’t need a warrant to get your information when companies offer it up willingly or offer it for sale. Pesky warrants are only for data that can’t be obtained through private companies.

This information is also gold for scammers who want to steal your identity. Knowing all the places you’ve lived sometimes helps them get past credit check identity verification steps, for example.

So, what you want to do is instruct these companies to delete your data and not collect anything on you in the future. If you’re in Europe or in select states in the U.S., you have the right to demand the removal of your data. Because of those laws, some companies offer those options to everyone. Other companies will deny you if you don’t live in a location with good protections.

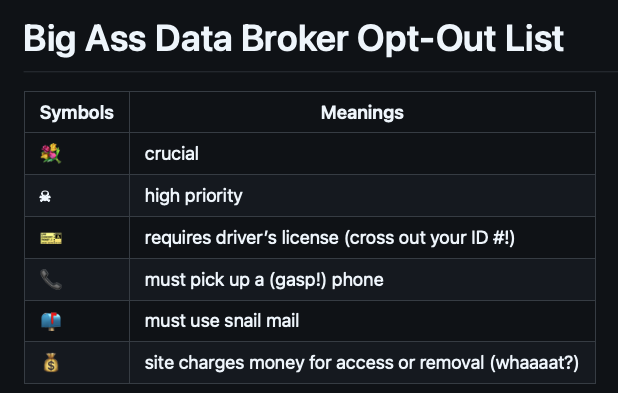

To opt out, you have two options. The first is to get a list of data brokers and manually go to each one to request the opt out. I’ve done this before, though the list has grown since I last attempted it. It’s time-consuming. I recommend starting with the list maintained by tech journalist Yael Grauer: Big Ass Data Broker Opt-Out List.

If you can afford to pay someone else, and the thought of going to each of those sites is overwhelming, you can use a service that submits opt-outs on your behalf. Prices range from $4 to $25 per month, and you can get deals around black Friday. There are several that I know of, including Kanary, DeleteMe, Optery, PrivacyBee, and Incogni.

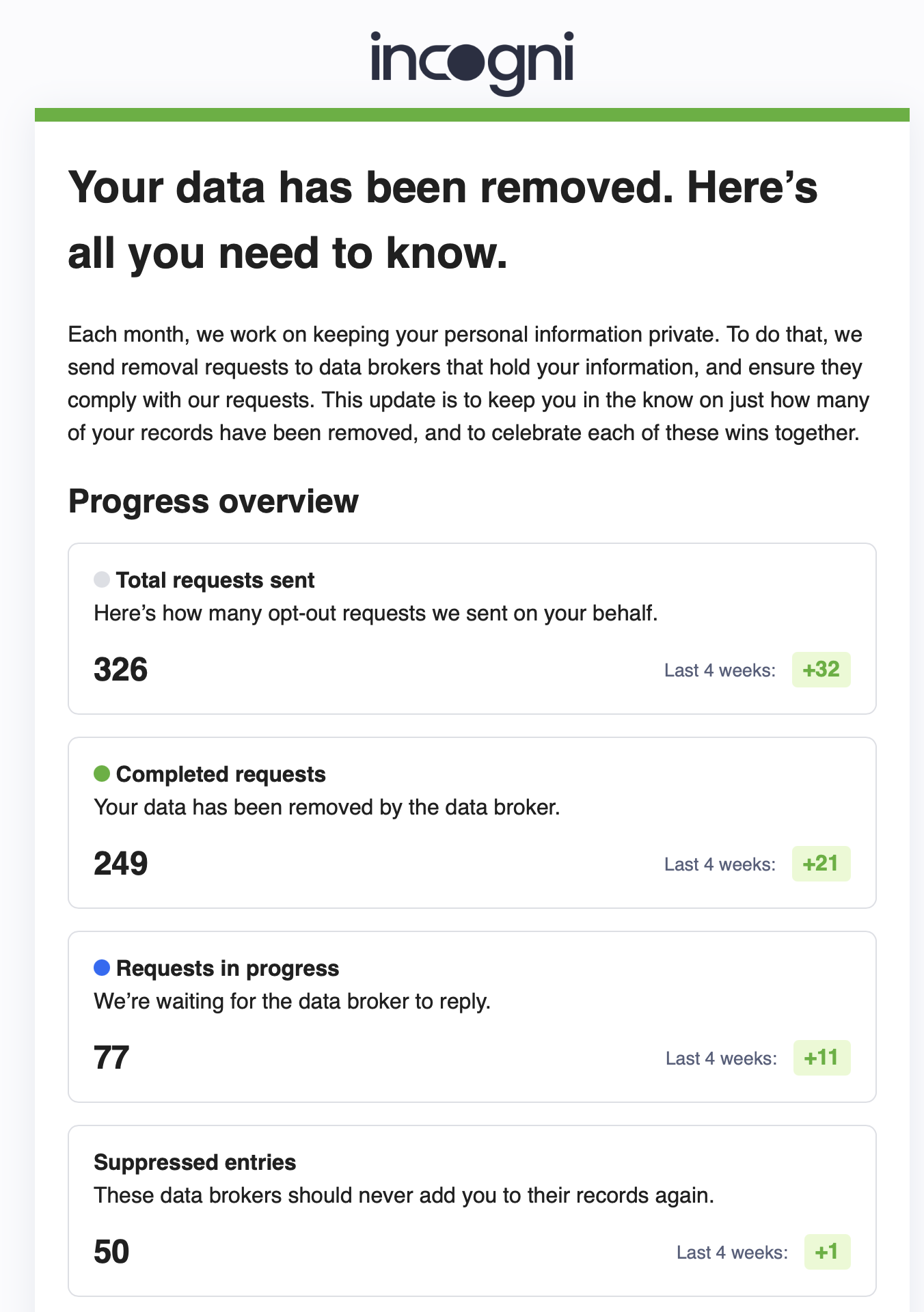

I’ve been using Incogni for about two years now. It isn’t a one-time thing because they keep adding new sites and resubmit requests as needed. Incogni has opted me out of around 250 data brokers so far and has attempted another 100 that have not responded to the requests. I’ve been pleased with them, but I haven’t tried any of the others and I don’t know how they compare.

PCMag reviewed a few and crowned Optery as the best, Incogni as the best for inexpensive removals, and PrivacyBee as the best for “comprehensive” removals. Using any of these is better than doing nothing, and because I can’t give a good comparison from personal experience, just pick the one that looks right for you.

One thing that feels bad here: in order to opt out, you have to give a lot of personal data both to the data broker and, if using an opt-out service, to that service, too. It feels like the opposite of what you’re trying to achieve. But they have to know who you are before they can delete you and that means they need data to look up your record. I wish I knew a way around that, but I don’t.

5.1 A Special Case: Get Out of Clearview’s Face Search Database

Companies like Facebook and Google use facial recognition to help you tag your photos with people’s names. This also helps them to learn who you are so they can recognize you across their products. They know your face even if you don’t upload photos, as long as your friends or family do and they tag you. By using those platforms, you’re effectively opting into that behavior and those trade-offs.

But then companies like Clearview AI come along, and they’re a bit different. You don’t use their service, but they still know how to associate you to your pictures.

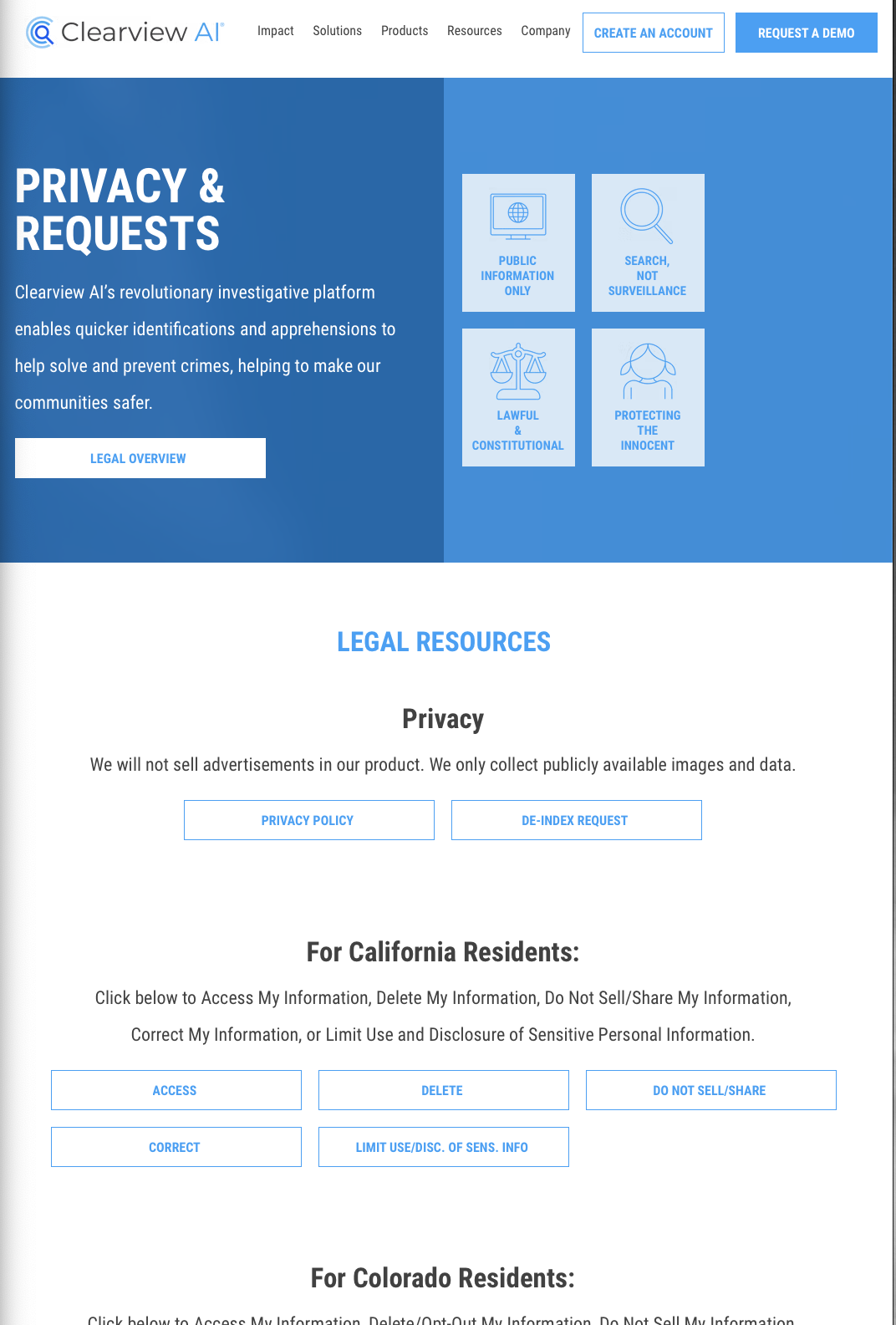

They scrape social media and the Internet at large, looking for photos (for example, social profile pictures) and names, then they build a database out of that information and sell it so others can identify you given a picture of your face. This type of commercial service is already being abused by private companies and by law enforcement.

You should absolutely opt out of Clearview AI, but be warned: they make it hard. In some cases, they require you to prove that your image is no longer public. They often refuse requests. They only offer deletion for people in certain states. Without Congress passing federal laws, this will remain a pain and, for some, an impossibility. 😞 Try anyway…

- Submit take down notices to Clearview AI using their “deindex” and “delete” processes

5.2 Switch to Cartoon-like Avatars

Although this isn’t strictly relevant to identity theft, I’ve included it because it relates to opt-outs and is a good privacy measure in general.

Your profile picture on social media (LinkedIn, BlueSky, X, or wherever) is a source of facial recognition information and can be used to make deep fakes of you talking. Instead of using your real photo for these profile pics, use an avatar of some kind. Perhaps use a picture of a fox. Or maybe a cartoon-like version of your face instead, which is what I do.

I paid $5 for a cartoon version of me after finding an artist with a style I liked over at Fiverr. You may need to do this and to take down public pictures of you, to the extent possible, before you can get removed from ClearView’s database.

I frequently speak at conferences that publish my photo and name, which makes it hard for me to protect myself from these services. If that’s the case for you, you’re a bit stuck. But it’s still worthwhile to take down what you can.

- Take down any social media profile pictures that show your face and replace with cartoon avatars or something else

Next in the series, we’ll cover how to protect your communications.