AI Coding Agents: Our Privacy Line in the Sand

How IronCore balances AI productivity with data protection

The New York Times is currently suing OpenAI, and as part of discovery, a judge has ordered OpenAI to preserve all chat logs indefinitely. That means every file, every code snippet, every secret accidentally pasted into ChatGPT is now evidence in The New York Times Company v. Microsoft Corporation et al., potentially discoverable by lawyers on both sides.

If you’ve been using AI coding tools with “zero retention” settings, thinking your data was safe, here’s the uncomfortable truth: it isn’t. And it won’t be for the foreseeable future.

At IronCore, we’ve spent the last year grappling with a fundamental question: how do we harness AI’s power without exposing our customers, our code, and our company to unacceptable risk? This is our answer.

I’ve said it before: AI is too dangerous to use and too powerful not to. But this isn’t about the dark corners of AI or the dangers of agentic workflows. It’s about policy: how to use AI when confidential data is at stake.

Most people focus on whether their data is used to train models. That matters, but it eclipses the bigger picture.

If you’ve been using AI coding tools with “zero retention” settings, thinking your data was safe, here’s the uncomfortable truth: it isn’t.

What we’re protecting

We have NDAs with customers and prospects, and duty of care for all information related to those relationships, from pricing quotes (which often have details on the scale of a customer) to internal documents and chats. We must know who can access confidential data and who has.

On the coding side, a lot of what IronCore builds is open source (typically using the AGPL license with commercial licenses available to paying customers), but we still have a fair bit of private source code. This makes it harder for someone to ride on our coattails and build a competitive solution.

We have other data to protect, too, like secrets such as API keys for various services, and personnel records, and so forth.

Breach response readiness

If a given service has an exploited vulnerability or an employee’s account is compromised (for example, a session cookie, OAuth token, or other 2FA bypass is stolen), we can figure out what they could access and, in most cases, what was accessed. From that information, we can understand what damage has been done and who, if anyone, needs to be contacted as part of breach disclosure.

When AI enters the equation

When you throw AI into the mix, it gets more complicated. If we were to enable Google’s workspace AI features or to allow arbitrary use of Anthropic’s Claude, then nearly any document could flow out to an LLM. That personnel record, which before lived in a single place, can easily live in multiple places in AI prompt contexts, histories, memory files, vector databases, and logs. Secrets that we thought were reasonably protected may now be duplicated into AI services in multiple places.

And we may not ever know exactly what’s there.

The uncomfortable truth about data retention

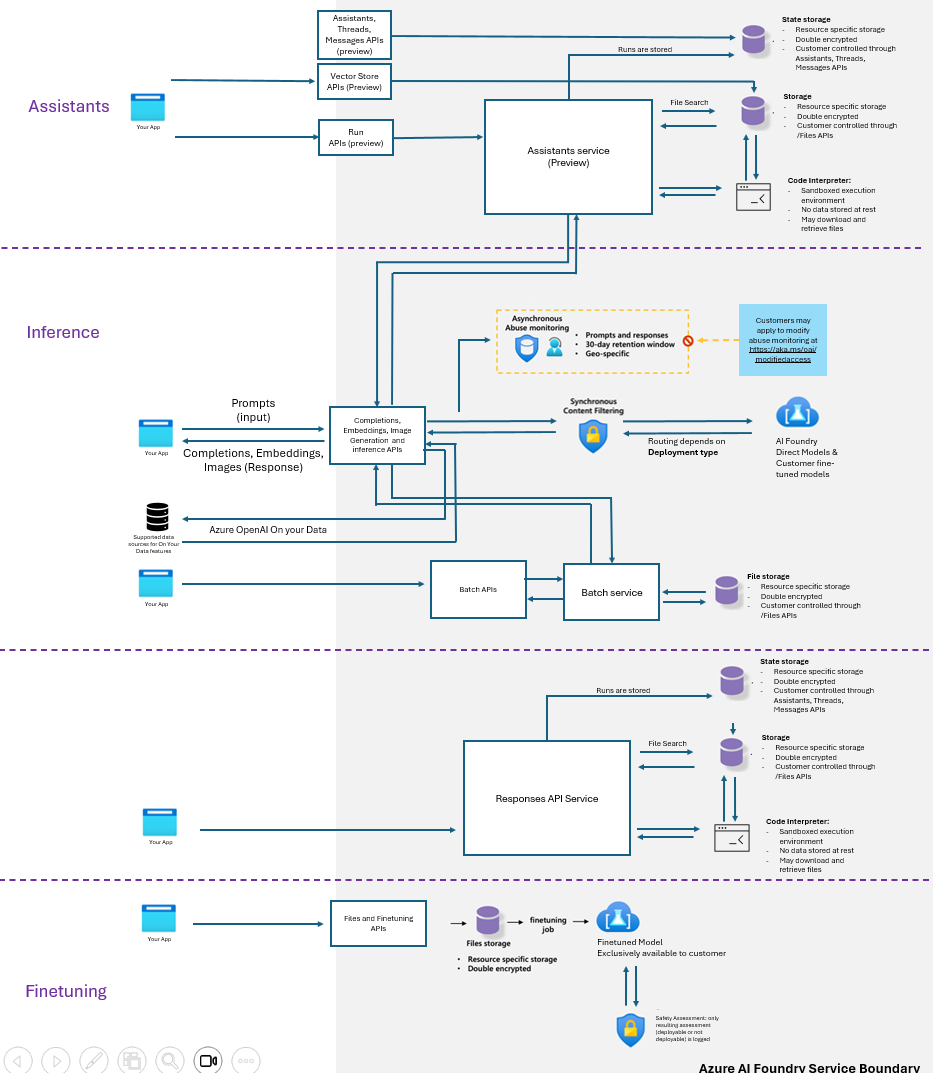

Suppose you, like me, turn off as much as you can around “memory” and model improvement settings (i.e. options that use your data for training). This is a good start, but unfortunately, not nearly enough. Under consumer-level plans, none of the major providers let you set a data retention period. Microsoft lets enterprise customers do this, but there are exceptions for possible abuse, which then gets held for 30 days.

If you’re using Claude Code, you would be forgiven for thinking there’s no server-side record of your queries. Conversation histories are stored locally in your ~/.claude folder by default, so that would make sense. And when you use the web interface, you don’t see any record of command-line Claude Code queries.

But assumption is the mother of all mistakes. Anthropic stores all of your conversations including all provided context for 30 days, and I’ve since confirmed with Anthropic support that this applies to Claude Code command-line. For web-based chats, they store them for 30 days after you manually delete them. And in either case, if you fail to opt out of your data being used for improving models, you can never get that data back.

And then there’s OpenAI. Remember that court order I mentioned at the top? Judge Ona T. Wang mandated that OpenAI preserve all output log data regardless of their consumer-facing deletion policies. Your files, secrets, and anything sent to OpenAI can’t be deleted for an undetermined time period. Whatever retention settings you’ve configured are essentially meaningless.

If you have a Google Workspace plan, then you have some ability to control whether Gemini has full, background, and transparent access to your data across Google Drive and other sources. You can also decide if conversation history is enabled and, if so, what the retention is (minimum 3 months).

That personnel record, which before lived in a single place, can easily live in multiple places in AI prompt contexts, histories, memory files, vector databases, and logs.

The ugly AI breach scenario

So if you or your co-workers are using these services with reckless abandon, then client data, personal data, secrets, and more could be sent up to these services. If one is breached, there’s no way to know what data of yours might be compromised and who should be notified. This is especially true if employees are using their own plans. Under enterprise plans, things are marginally better, but still problematic.

For IronCore, this makes it hard to keep contractual promises or to understand our risk levels. We’re also a bit dubious about security practices of some of these companies and where they prioritize privacy versus the desire to suck up, retain, and use as much data as they can.

Our approach: finding the balance

But we can’t ignore these tools. We’ll lose out to companies that are faster because they’re willing to turn a blind eye to the risks (or to people not educated enough to even understand the risks they’re taking). So where do we draw the lines?

For us, we want to be explicit about when private data goes to these services and what data is allowed. We’ve developed policies for our engineers and for the rest of our company. And we’ve added enforcement for the rules when possible.

We’ll lose out to companies that are faster because they’re willing to turn a blind eye to the risks.

Our policies

In case it’s a helpful starting point or inspiration to others, here’s our current AI policy.

1. No exposure of confidential information

AI agents must not be provided with non-public product plans, strategic documents, design specifications, roadmap content, financial data, HR data, customer data, non-public intellectual property, or any unpublished material describing future features, priorities, or intentions. This includes planning artifacts, architectural discussions for unreleased work, and any text that could reveal future product direction. Coding assistants are not allowed to process code bases that aren’t open source, though small code snippets may be sent with specific questions. No secrets, such as API keys, should ever be shared with a model run by a 3rd-party. Care must be taken to expressly forbid the reading of files such as

.envand folders such as~/.ssh.

Engineers are allowed to feed entire code repositories to LLMs and agents only if the code base is already public. Asking questions about errors or small code snippets, though, is something we allow even for our private repositories.

Private documents that are considered internal and confidential should never go to 3rd-party LLMs, which means coding assistants cannot be run in directories that have these files, and AI chatbots and agents cannot be connected to any services that harbor confidential information, like Google Drive. This also means that while we can use Claude Code from the terminal, we don’t want to give Anthropic access to our GitHub. Thus, we can’t use their web interface for coding because creating that connection which could expose our private repositories is against our policy.

Our employees who aren’t writing code are free to share draft marketing copy and other communications that are or will be public. Our marketing folks aren’t particularly restricted. Our admin folks, on the other hand, work extensively in the personnel and finance domains and don’t have many opportunities to use AI within our policy.

2. No persistent storage or memory on AI platforms

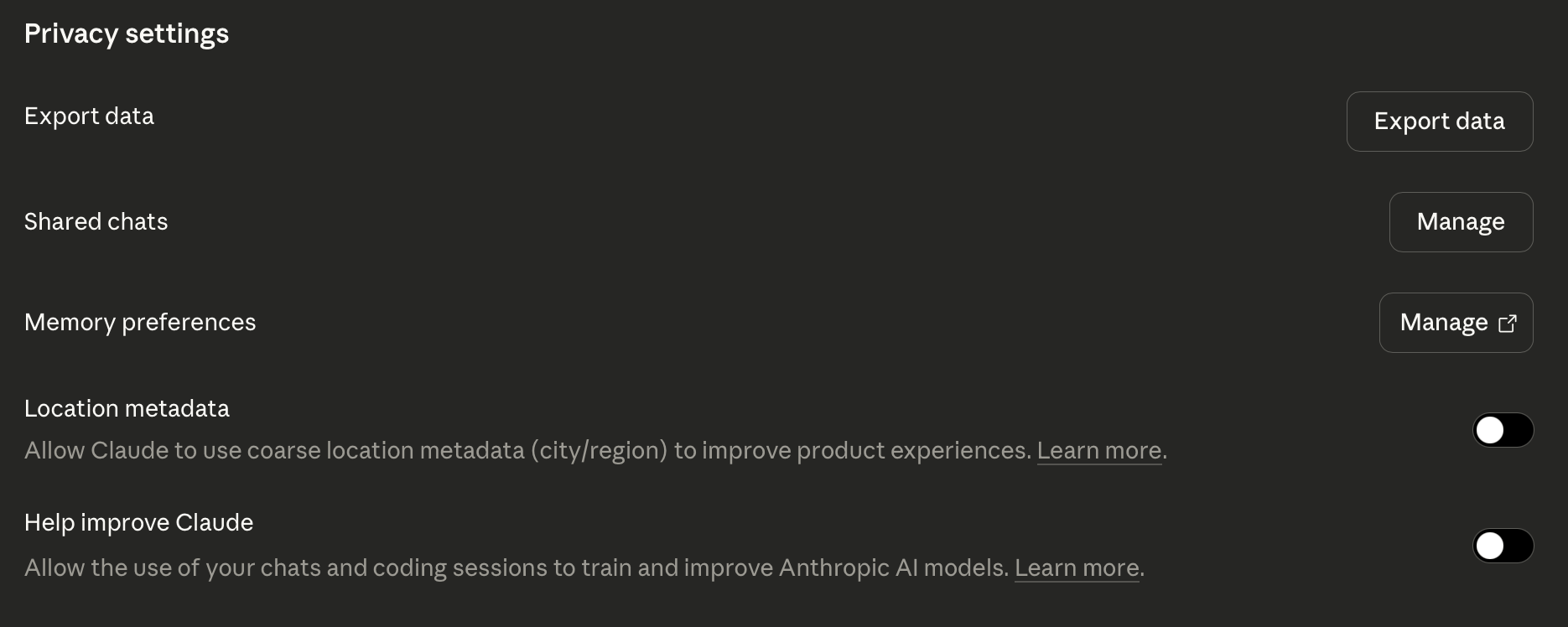

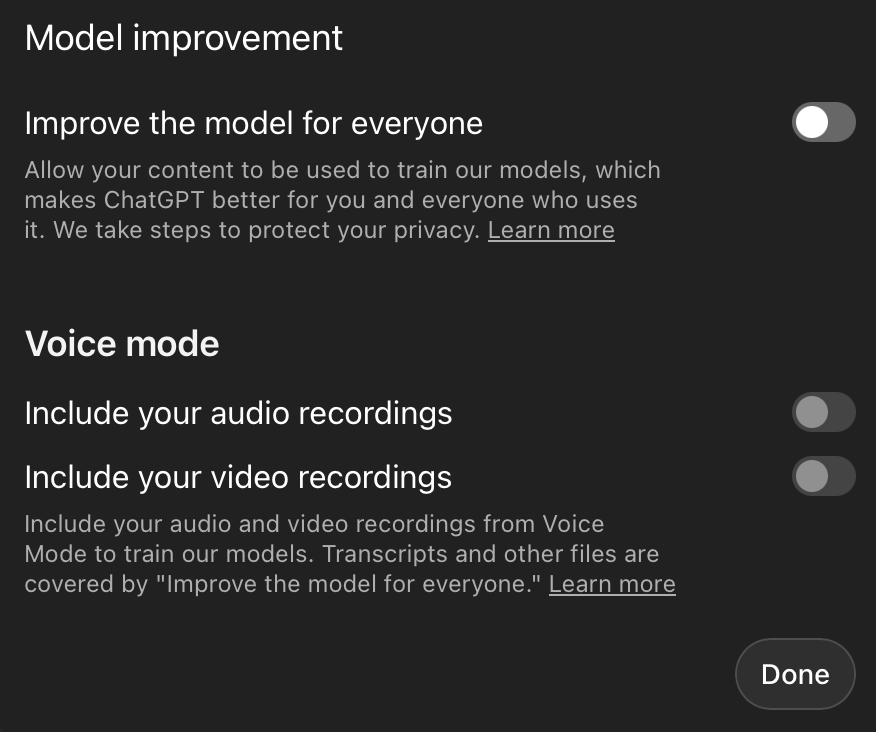

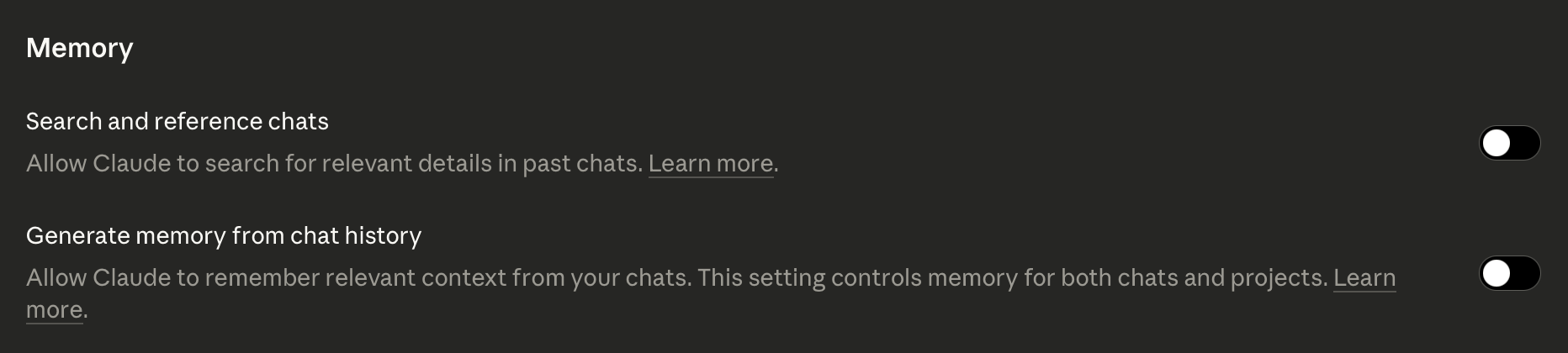

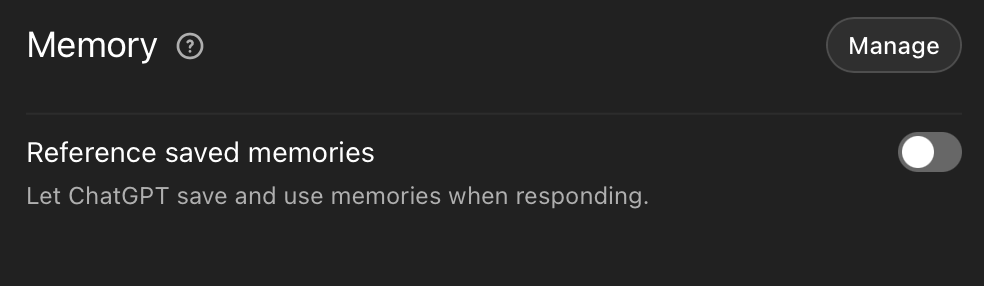

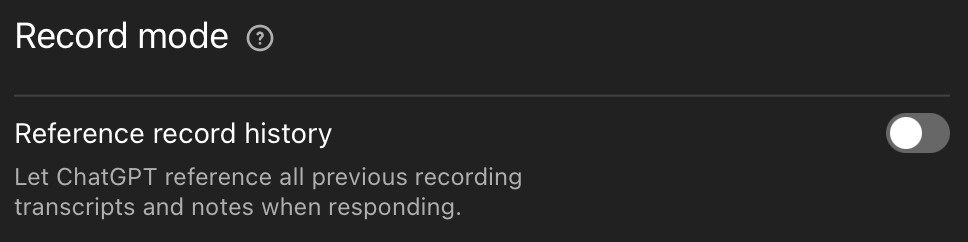

Only AI services that maintain no service-side long term storage, memory, or training impact from submitted data may be used. Settings to “Help improve Claude” or “Improve the model for everyone” or similar must be turned off before any use. Users must ensure the chosen platform operates in a stateless manner for all interactions. When memory is desired, it should be maintained as text state to be provided later, such skill descriptions or similar files maintained on client-side storage.

AGENTS.md,GEMINI.md,CLAUDE.mdand similar files that are stored in GitHub repositories as per-project memory are also okay provided they don’t contain any secrets and don’t imply 3rd-party LLM use in private repos (see policy #1).

One of the biggest troubles with current AI is its penchant for automatically grabbing context and sending it off to other people’s servers. The user frequently doesn’t know what’s being sent or what might be included, much less how long it will be kept or how it might get used. Any employee using these tools MUST take control of their preferences to manage these risks as much as possible.

The idea that these services can store anything and everything they see and then tap into it at will forever is, frankly, horrifying. Those features can no doubt be powerful, but they introduce huge inherent risks. And the dangers extend beyond the possibility that private data might resurface later.

There is now an entire class of attacks that seeks to capture prompt injections in “memory” so things like data exfiltration commands can be automatically triggered perpetually. It’s the prompt injection equivalent of a rootkit gaining persistence. We must guard against this possibility.

3. Private AI okay on private data

When using coding agents or agentic AI over entire files or repositories that aren’t public, use our self-hosted AI models instead of models hosted by AI platforms. Models that run on your local machine, such as transcription models, are also okay as long as you’re sure the data is processed locally and not uploaded to a 3rd-party service.

Although we don’t currently have the hardware required to execute the more performant AI models, some tasks can be done reasonably well by self-hosted models. We are weighing whether or not to invest in hardware that can run bigger and better models to expand the set of tasks we can execute locally.

4. Restrictions on automation and deployments

AI agents must not automatically push code to any main or protected branch of a repository. They must not participate in deployment or release pipelines, including triggering, approving, or executing deployment actions. The use of command line tools such as

gcloudand direct access to production databases is forbidden. AI agents may be used in the code review of deployment related code, but all suggestions must be reviewed by an engineer. An AI review of code is never sufficient without a human also reviewing and approving code changes.

LLMs make mistakes. In sandbox environments or on tasks that aren’t critical, these are often things that we can recover from without too much trouble. But when it comes to production systems, we’re not willing to risk AI errors turning into downtime.

We treat our production systems as published code. Updating or changing settings usually requires committing code, having it reviewed, and then merging it before it can take any effect. This fixes whole classes of potential issues if an attacker gains access to our source code or wants to make changes in production. Very little can get to production without at least two people participating. And we don’t want that or our quality standards to be undermined in any way by AI.

5. Employees are responsible for their actions

Employees are responsible for reviewing all content before submitting it to an AI agent to ensure it does not include confidential data like roadmap, planning, or strategic information. If employees are uncertain, they must not share the content. Each employee must understand the scope of the agent and when it doubt, ask for help. Additionally, when an engineer uses AI to assist on a task, it is the engineer who is responsible for the quality, reliability, and maintainability of that code.

We employ people, not agents. AI agents can’t be held accountable for their actions. These are helper tools and people are ultimately responsible for the results they use or share, whether or not they were assisted by AI. There’s a certain amount of unreliability in AI that can bite you if you’re not careful. In management, there’s a saying, “you can delegate authority, but not responsibility.” That applies equally well to the use of AI tools.

Guardrails we’ve built

Our Engineering team shares a private tool built on nix-pai (itself derived from the personal AI infrastructure project). It’s fundamentally Claude Code with a set of stock settings, permissions, and skills. These are IronCore-specific skills, including this AI policy, a skill for each language we use for development, brand guidelines, and others. The tool detects if it’s being run in an open source library or not, and it reminds the user to use private AI if the code isn’t public. We’ve also built in as many permissions and other limits as we can.

You can delegate authority, but not responsibility.

The built-in permissions forbid the most dangerous commands, like rm -rf /, and the use of infrastructure tools like gcloud. They force the user to always approve git push commands, don’t allow the bypass of permissions with the --allow-dangerously-skip-permissions parameter, and so on.

For private AI, we have a machine that all employees can access that runs mid-size open source models. It works for quite a few tasks, but not all. We’ll write more about this later.

The line

The line is fluid right now. The tools are changing fast, the capabilities are growing. We’ll likely determine specific cases where we require full sandboxes, possibly on platforms like Sprites, as a way to grant more capabilities and permissions to these tools while minimizing the repercussions when they get confused or they are poisoned.

Wherever you draw the line, if you’re setting policies and working to find ways to enforce them, you’re already on a better path than the 63% of organizations that lack any AI governance policies (per the Cost of a Data Breach Report).

We’d love to hear from you if you have other ideas on where to draw the line or how to enforce it. On the topic of AI security risks, check out our paper on AI Shadow Data or learn about how we protect data in AI systems.